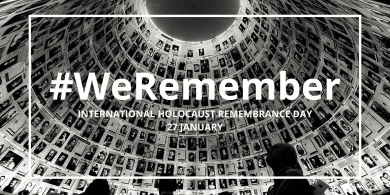

#WEREMEMBER: HOLOCAUST TESTIMONIES

The stories of Holocaust survivors are a clear reminder of the need to combat injustice, hate motivated policies and discrimination.

By the end of World War II, nearly six million Jews had been killed as a result of the Nazi regime’s systematic policy of genocide. Along with Jews, many other groups were targeted, imprisoned and/or murdered, including Roma, the disabled, Slavic people, communists, socialists, Jehovah’s Witnesses and homosexuals.

Although 77 years have passed since the war, issues as antisemitism, Islamophobia, racism, discrimination and xenophobia continue to divide societies all over the world. The testimonies and stories of the survivors have a vital place in keeping the memory of the Holocaust, one of the most unimaginable crimes in human history, alive and preventing similar suffering.

The path to the Holocaust

Genocide did not come out of nowhere: The process was constructed in small steps with words, discourse, and the discriminatory practices and laws that followed, long before ghettos, death and concentration camps were set up.

Born in 1927, Otto Rosenberg grew up in Berlin with his grandmother and two siblings, was from the Sinti community, a Roma population of Central Europe. Rosenberg expresses the exclusionary discourse he was exposed to in his daily life: “The children… bumped into me and called me names, that I was a dirty gypsy and much more.” [1]

Once the Nazi government came to power in Germany in 1933, they had begun to fulfil their commitments to “Aryanize” the country and to segregate and marginalize the Jewish population. They encouraged the boycott of Jewish businesses, which where stigmatized with the Star of David or the word “Jude”. New laws were enacted to restrict all aspects of Jewish life, while propaganda posters and films suggested that Jews were ‘vermin,’ comparing them to rats and insects.

Born in Breslau, Germany in 1925, Frank Cohn describes his experiences after the enactment of antisemitic laws:

One day, going to school, I was chased by a group of kids yelling, ‘Jewish boy!’ But I was a fast runner and eluded them. It was on that day that my parents decided to move me into a private, Jewish school.

Our life in Breslau became increasingly more uncomfortable. We had some German friends with children, who I played with, but they terminated contact as soon as Hitler came to power. There were no public restaurants where Jews could eat. Most had signs ‘Jews Not Welcome’ or ‘Jews Prohibited.’[2]

Deportation to ghettos and concentration camps

To facilitate their subsequent deportation and to enable the Jewish population to be gathered and monitored, the Nazis set up ghettos, temporary camps, and forced labor camps for Jews. Over time, Nazi persecution became more and more radical. This radicalization resulted in what the Nazi leaders called the “Final Solution”. The “Final Solution” was the organized and systematic mass murder of European Jews.

Marian Kalwary, who was forcibly sent to the Warsaw ghetto in 1950, describes the rapidly growing population of the ghetto, where diseases spread, electricity was cut off, and hunger reigned:

Walking—or rather loitering—around the ghetto, the streets were horrendous. I remember the shocking scenes of dead bodies covered with newspapers lying in the streets, as indifferent crowds passed right by the skeleton bodies. I remember hundreds, perhaps thousands, of hungry people begging for bread.[3]

Joseph Moses Lang, who was deported to Auschwitz with hundreds of others on his 17th birthday, June 7, 1944:

Upon arriving at Auschwitz, men and women were immediately separated and this would be the last time that Meir and I would ever see our mother and sister. For the next several days, the Nazis undertook the process of sorting out the men to find strong workers. The young, old and weak were sent elsewhere. One of the soldiers asked me in German, how old I was and I lied and said ‘19’ while standing on my tiptoes in order to look taller.[4]

Irene Safran, who was sent to the Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp with her family, describes her encounter with the concentration camp doctor, Joseph Mengele, in her memoirs:

We looked like animals in a cage with our shaved heads and the ripped rags wrapped around our emaciated bodies. ‘When will I see my mother?’ one woman finally asked in a very low voice, almost like a whisper. ‘In a few weeks, don’t worry,” Mengele answered politely and pleasantly. ‘When will I see my little girl?’ a second woman got the courage to ask, when she saw that the first woman hadn’t been beaten for speaking up. Mengele gave her the same answer. We almost believed him. He looked so elegant and civilized compared to us that we felt like we were looking at God. Of course, he meant that we’d see our loved ones in a few weeks when we joined them in heaven after going up in smoke from the crematorium.[5]

At this point, it is important to remember the rescuers who risked not only their own lives, but also the lives of their families, thereby keeping hope alive. For instance, after the occupation of the Netherlands by Germany in 1940, one-year-old Alfred (Al) Münzer was entrusted to the family’s neighbour Annie Madna, while his sisters were placed with two Catholic women, who were also neighbours. [6] Similarly, in the fall of 1943, Refik Veseli, a sixteen-year-old Albanian photography student, received permission from his parents to hide Mosa Mandil and his family, Jewish refugees from Yugoslavia, in the Veseli home. There, from November 1943 until the liberation of Albania in October 1944, the Mandils received shelter and avoided deportation.[7]

Survivors of the Holocaust

By the end of the war in 1945, in the aftermath of the Holocaust, survivors faced the traumatic reality of losing their entire family and community. Those who survived had to cope with the traumas of the Holocaust and the challenges of rebuilding their lives. Jakob Blankitny says that for the survivors, the numbers tattooed on their arms, as soon as they entered Auschwitz and became their identities from that moment, are a daily reminder of the horror they had to go through.[8]

Born in Czemierniki, Poland in 1923, Joseph Mandrowitz describes the scene he encountered upon his return to his birthplace in 1993, years later:

When I finally returned to Czemierniki in 1993, despite the years in which Jews had lived there I could not find a trace either of my family or of Jewish life. Even the cemetery where my grandfather had been buried had been razed. The synagogue was gone. I went to ask the local priest, who said they had taken the tombstones and crushed them for building materials or something like that. I believe they deliberately destroyed any sign of Jewish life so as to be rid of us for ever.[9]

Felix Horn, who immigrated to the United States after the war, expresses the effect of the trauma he experienced on his adaptation process:

Americans, first time I’d seen Americans, life full of music, and laughter. I didn’t know what it was, I didn’t know how to behave. I was afraid of this thing, I thought it’s sacrilegious, to laugh and to smile and go to nightclubs and to coffeehouses, I, I couldn’t, couldn’t cope with it, you know, I was not ready for it.[10]

Therefore, remembering the victims, commemorating the Holocaust, and Holocaust education remain a universal necessity to strengthen individuals’ resilience to policies motivated by hate. Genocide does not come out of nowhere, it manifests as the culmination of uncontrolled discrimination, racism and hatred over a period of time. Talking about genocide is an assurance that similar suffering will not happen again, and in particular, to be alert for signals that could lead to a cycle of systematic violence. Undoubtedly, the courage and strength of those who witnessed the systematic and industrialized murder of millions of people with their testimonies also shed light on today’s problems that hinder living together:

We who survived Auschwitz or other concentration camps advocate hope not despair, generosity not bitterness, gratitude not violence. We must reject indifference as an option.[11]